Source: CBC News

Source: CBC News

By Daniel Schwartz

May 27, 2015

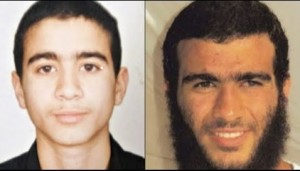

In his first full-length interview since being released from a Canadian prison, Omar Khadr, the former Guantanamo detainee, says he wants to be seen as “just the next Joe on the street who nobody knows and nobody gives a second look or thought to.”

But having come from the family he does, and having spent the last 13 of his 28 years in custody and in the eye of an international storm, Khadr also acknowledges he will face a considerable degree of public suspicion.

“People are just going to think that I’m fake. You go through a struggle, you go through a trauma, you’re going to be bitter, you’re going to hate some people. It’s just the normal thing to do — and this guy, not having these natural emotions, is probably hiding something.”

Interviewed by the Toronto Star’s Michelle Shephard, the author of Guantanamo’s Child: the Untold Story of Omar Khadr, Khadr talks about his al-Qaeda experiences and the firefight with U.S. soldiers in 2002 that led to the death of army medic Christopher Speer and to Khadr himself barely hanging on to life, as well as about his decade at Guantanamo and his post-release “freedom high.”

The interview is part of a 44-minute documentary, Omar Khadr: Out of the Shadows, a collaboration between the CBC, the Toronto Star and White Pine Pictures.

WATCH: Omar Khadr: Out of the Shadows

Released on bail on May 7 while he appeals his U.S. military conviction, Khadr says he worries whether his new freedom is going to last or wonders if he is “just hungry to experience everything all at once.”

An al-Qaeda child

In the documentary Omar Khadr: Out of the Shadows, Khadr talks about the firefight with American troops in 2002, his decade incarcerated at Guantanamo and his new-found ‘freedom high.’ (Nathan Denette/Canadian Press)

Born in Toronto in 1986, Khadr spent his childhood in Canada, Pakistan and Afghanistan, where his father, Ahmed Khadr, was a devotee of then al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.

After Sept. 11 and the fall of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, Khadr’s father handed the boy over to Taliban fighters to serve as their translator.

That was how, at 15, he came to be involved in a firefight with U.S. forces, during which he has admitted to throwing a grenade and was seriously injured himself. Three months later, he was taken to the U.S. military installation in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where he stayed until his transfer to a Canadian prison in 2012 after pleading guilty to five war-crime charges and receiving an eight-year sentence from a U.S. military commission.

In the documentary, Khadr and others talk about the torture he endured before and after that transfer.

He also talks about how one prisoner would be taken from his cell for a few days and the other inmates would hear constant screaming. “Then he would come back just a destroyed person, so you can only imagine what happened to him.”

About his own prison time, Khadr says it gave him a lot of time to think and contemplate. He acknowledges that he was a mess and would act and talk like the other inmates he was around during those first few years.

At one point, Khadr talks about how he changed his own thinking about one guard who was especially cruel to him.

“If a person can inflict pain on another person and find pleasure in that, that person must be going through a lot of problems,” he says. “He’s probably living in worse pain than the thing he’s causing me.”

Khadr says that while in prison he tried to avoid dwelling on the past.

“It was either that or be engulfed in hate and misery and think of how bad life is.”

Instead, he says, he “tried to think about things that would hopefully make my life, and hopefully the life of people around me, better.”

‘Give me a chance’

In the weeks since his release, Khadr has been learning, or relearning, about things like how to open a window, and “how immense the sky is.”

Now, he says, his wish is for people to just give him a chance. In the documentary he explains, “For the longest time, all I would tell anybody is that I wish that I could just get out of prison and just be the next Joe on the street.”

That is essentially what he also told CBC News in a 2008 interview conducted in writing while he was still in Guantanamo: “I just want to be as normal as any normal unknown Canadian.”

In the documentary, Khadr reflects on what, hypothetically, he would change about his past. “I would change the firefight maybe, but wouldn’t that change a lot of things?

“I’ve come to know wonderful people, I’ve come to know myself because of this experience. It’s a very hard trade for me.”

The 2002 firefight

When he does talk about the 2002 firefight in Afghanistan, Khadr’s answers suggest he is not sure himself what happened, whether he threw the grenade that killed Sgt. Speer.

Many grenades were thrown during the firefight. Khadr, then 15, thinks he may have thrown one grenade toward the end of the battle; at a point when he couldn’t see out of one eye, could barely see out of the other and had multiple wounds.

He doubts his own memory of the events and points to testimony that the Americans found him under the debris and that he couldn’t have thrown the fatal grenade, and that no one claims to have seen him do it.

“I always hold to the hope that maybe my memories were not true,” Khadr says.

Interrogator Damien Corsetti, who saw Khadr at the U.S. airbase in Bagram, Afghanistan, remembers he had a hole the size of a Coke can in the back of his head. Khadr remembers losing consciousness for a week.

“Is my memory more accurate than a soldier who was actually there?” Khadr asks.

Then he adds, “On one side, I killed another person, and on the other side I didn’t, so it does make a huge difference.”

The guilty plea

As part of a plea deal, Khadr did plead guilty before a U.S. military commission in 2010 to the death of Sgt. Speer.

In the documentary, his lawyer Dennis Edney says Khadr resisted the guilty plea and he had to persuade him to agree to the deal.

“One of his first thoughts was ‘the Canadian public will believe I’m a terrorist,’ and I said to him if you don’t do a plea you’ll spend the rest of your life here” in Guantanamo.

David Glazier, an American law professor and military commissions expert, told CBC News that, “under the circumstances, that was a shrewd tactical move,” and that Edney represented Khadr very well by having him agree to a guilty plea.

Speaking the day Khadr was released on bail, Glazier noted that things were stacked against Khadr at the time.

His statements, extracted “under torture,” were ruled to be admissible, and a trial panel of U.S. military officers “hand-selected for their reliability to the government’s views, was going to convict him and probably return a life sentence.”